Mineral Exploration

Sample preparation for the XRD Scanner - an unique look behind the scenes

7:10

Europe faces various choices and challenges in terms of mining and the availability of raw materials. The 2023 European Critical Raw Materials Act was drawn up to break the current deadlock.

The energy transition is essential for addressing climate change. To achieve this, the world also needs a materials transition.

The underlying technology requires large quantities of 'uncommon' raw materials, such as lithium, nickel, cobalt, and rare earth metals. For many of these materials, there are concerns about security of supply, the sustainability of mining, and dependence on a limited number of countries.

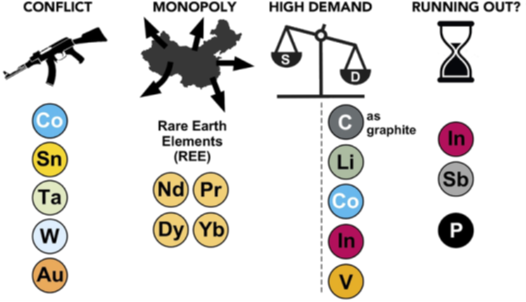

Examples of raw materials whose security of supply raises concerns.

The extraction, processing, and refining of the necessary raw materials demand production means, energy, and labour.

Moreover, these processes result in CO2 emissions and negative effects on nature and the environment.

From an economics perspective, these raw materials are, therefore, scarce already. This scarcity is exacerbated by the energy transition, as supply struggles to keep up with demand.

However, in addition to economic scarcity, there are two other significant forms of scarcity.

The first is geological scarcity: is there enough of certain raw materials in extractable form to meet demand?

Secondly, there is geopolitical scarcity. Some raw materials are only mined, processed, or refined in a few countries, leading to undesirable geopolitical dependencies.

Besides these two types of scarcity, a lack of social acceptance of the mining industry also plays a key part.

The geological reserves of raw materials on our planet are finite by definition.

Furthermore, only the shallowest part of the Earth's crust, typically the first kilometre, is accessible for mining.

Nonetheless, there currently appears to be no geological scarcity for any particular raw material. According to geologists, this is expected to remain the case for the coming decades.

The notion of geological scarcity is underpinned by two concepts: reserves and resources.

Resources refer to the total amount of minerals located in the Earth's crust at a specific site. Reserves represent the portion of those resources that are proven at the highest level of confidence, and can be extracted in an economically viable manner.

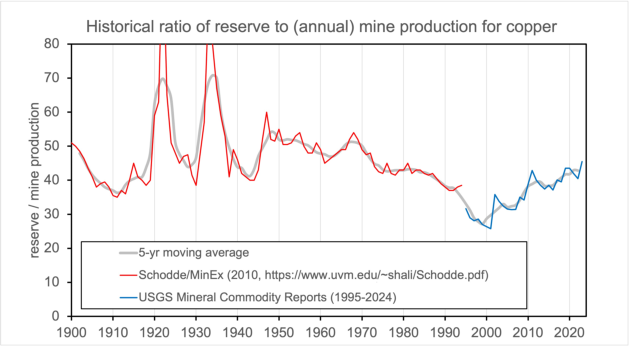

Summing up all global reserves for a particular material and dividing this total by the annual extraction rate gives the reserves-to-production ratio (R/P ratio).

For most raw materials, this ratio suggests a supply lasting for several decades. This does not even mean that the resources will be depleted after that period. The total resources are much larger than the reserves, and each year, new reserves are added to replace the amount extracted. New deposits are discovered, and through further investigation, they end up being officially classified as reserves.

This explains why the R/P ratio for copper, for instance, has remained stable at around 40 since 1900.

Innovation in the efficiency of extracting raw materials from ores also plays a role.

For example, in the early 20th century, only ores containing more than 3-4% copper were economically viable.

Today, mining companies routinely work with copper ores containing less than 1% copper.

A downside of these innovations is that the environmental footprint of mining keeps growing. Extracting and processing ores with lower concentrations leads to more waste and requires greater amounts of energy, water, and chemicals.

The International Energy Agency notes that the extraction and refining of raw materials critical for the energy transition are far more geographically concentrated than is the case for fossil fuels.

While raw materials such as lithium, cobalt, and rare earth metals remain widely available on the global market for the foreseeable future, the desire for strategic autonomy creates scarcity.

This also applies to so-called conflict materials – raw materials whose extraction is sometimes associated with child labour and other human rights violations. Examples include tin, tantalum, tungsten, gold, and cobalt.

Perhaps the most important factor influencing raw material scarcity in Europe is the lack of a social licence to operate from local communities. There is significant public resistance to mining — and the associated polluting industries such as smelting, refining, and recycling of raw materials — and many potential new projects face opposition.

For many mining companies, this represents one of the biggest business risks. While raw materials like lithium and rare earth metals are abundant in Europe's subsoil, and it is strategically desirable to extract them within Europe, the absence of a social licence makes these resources even scarcer.

To address these various forms of raw material scarcity, the European Commission has introduced the Critical Raw Materials Act. It identifies 34 'critical raw materials' of significant economic and societal importance but whose supply security may be at risk. Of these, 16 are designated as 'strategic raw materials'.

The Critical Raw Materials Act sets ambitious targets for the extraction of these strategic raw materials within Europe, as well as for recycling.

It also aims to speed up decision-making (with less public input) for strategic projects in the field of raw materials, partly in response to the issue of social licence.

Geologically, there appears to be no scarcity of the vast majority of raw materials, and there should be enough to meet the expected demand of the energy transition.

However, the desire to maintain strategic autonomy, concerns about conflict materials, and societal aversion to mining and related industries in Europe have created an expectation of scarcity for critical and strategic raw materials.

This could delay the energy transition, and Europe will have to make some uncomfortable choices regarding its future raw material supply.

This article is a teaser of a published journal article and has been translated from Dutch. Click here to read the original article: Dijkstra, A. H. (2024). Zijn de grondstoffen voor de energietransitie schaars? In Natuurkundige voordrachten 2023 - 2024 (Vol. 102, pp. 45-50). (Natuurkundige Voordrachten; Vol. 102). Koninklijke Maatschappij voor Natuurkunde onder de zinspreuk Diligentia.