Disaster Risk

12 challenges in protecting displaced people from flood risk

7 min

Imagine you get this message:

"Tomorrow afternoon, there will be heavy wind gusts of 100 km/hour".

Now, imagine instead that you get this message:

"Due to strong winds expected tomorrow afternoon, there is an 80% chance of trees falling in neighbourhood A, which may cause travel disruptions from road X to Y. Expect delays in travel time up to 1 hour."

Wouldn’t that be much more useful?

This is the essence of impact-based forecasting (IBF), which goes beyond simply predicting the weather, to forecasting the potential impacts on daily life, helping you and decision-makers prepare more effectively for adverse conditions.

Traditionally, national hydro-meteorological services have focused solely on providing timely and accurate weather-related information, and they’ve become pretty good at it. But knowing what the weather can or will do, rather than what the weather will be, is much more actionable for people and decision-makers, enabling targeted, cost-effective, and informed decisions. Although the development of IBF is still in its infancy, it’s likely to advance rapidly and the opportunities are enormous. Will impact-based forecasting save the world?

The impacts from a specific weather event depend not only on the weather itself, but also on local vulnerability and exposure factors. Vulnerability refers to how susceptible a community or area is to harm from weather events, while exposure indicates the presence of people, infrastructure, and assets in the affected area.

Let me illustrate with some examples.

1. The same storm bringing heavy rain might cause severe flooding in a densely populated area with poor drainage, while a region without any people and with lots of nature might experience minimal impact or no flooding at all.

2. Strong winds of 100 km/hour in a neighbourhood with dry, ageing trees, may cause a lot of damage. In another neighbourhood with younger trees and less dry grounds, the same winds would cause fewer disruptions.

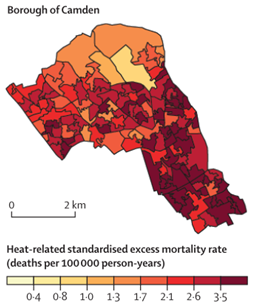

3. For extreme heat, the same temperatures could lead to severe heat illnesses in one neighborhood because of old housing and population- vulnerability, and no problems in another.

In conclusion: when forecasting impacts, we have to combine meteorological information with local vulnerability and exposure data.

Source: WMO, n.d.

Imagine we could forecast the impacts of a heatwave, pinpointing which neighbourhoods are most likely to experience heat-related health risks. The Red Cross could then focus its resources and volunteers on those areas, and take actions such as door-to-door campaigns and distributing water.

Similarly, that we could forecast the percentage increase in emergency room admissions for a specific municipality – or predict the likelihood that a large number of ambulances will be needed during a certain day. That detailed and local information could tremendously help emergency services, allowing them to allocate resources more effectively, especially when they’re limited.

Source: Gasparrini et al. (2022)

Next to allocating resources more efficiently, prioritizing areas that are likely to be most affected, and maximizing the effectiveness of response efforts, there are other benefits as well. Recent research on the topic has shown that people might be more likely to take action if the impacts are effectively communicated. By communicating not just the weather forecast but also its potential impacts, IBF thus helps to raise public awareness of the risks of upcoming weather events, thereby fostering a culture of preparedness.

Still, impact-based forecasting might not be as easy as it seems. First of all, a large amount of data is required, not only on the weather event, but also on vulnerabilities, exposure, and impact, and preferably on a high spatiotemporal resolution. This type of data simply doesn’t exist in many places in the world, such as the low- or middle-income regions of Africa, Asia and Latin America. In addition, all these datasets come with their own uncertainties, and combining them further increases the uncertainty of a forecast. Next, using historical data to build impact models might not allow us to accurately predict impacts during scenarios or weather extremes that are by definition unprecedented, and (non-linear) changes in socio-economic factors are not always taken into account. This can partly be solved by updating our models regularly with new data.

It is also important to verify our forecasts. But if IBF is very effective in stimulating preventive measures, the actual impacts of the weather event will be less severe than initially predicted. Forecasters must therefore carefully analyze both the predicted and observed outcomes, taking into account the effectiveness of mitigation efforts.

Last but not least: who is responsible for developing IBF? Meteorological institutes are of course a crucial player, being the experts on forecasting the weather. They must do its homework by providing a more localized view of the weather, especially in cities and nature areas, using historical data and forecasts. But they can’t do it alone. Developing accurate and useful impact-based forecasts clearly requires collaboration among various stakeholders, who often don’t speak the same language. ‘Collaboration’ sounds very nice, but can be difficult and time-consuming in reality. Organizations still work in silos, have varying budgets, and have different priorities, making it challenging to align efforts and integrate data seamlessly. Overcoming these barriers requires strong leadership, effective communication, and mutual commitment towards shared goals. After all, an impact forecast only becomes valuable when it leads to decisions that create better situations for society. To do that, we have talk to each other more often to learn each others’ language.

In an era of increasingly severe and unpredictable weather events, traditional forecasting methods that focus solely on predicting weather conditions are no longer sufficient. Looking ahead, advancements in technology, such as artificial intelligence and big data analytics, are expected to enhance the accuracy and utility of impact-based forecasting. Greater collaboration between meteorological agencies, health institutes, disaster management authorities, and communities will also play a crucial role in refining and implementing IBF strategies. The WMO published its first Guidelines on Multi-hazard Impact-based Forecast and Warning Services in 2015, with an update in 2021 due to the fast-paced advacements in the field.

Impact-based forecasting represents a paradigm shift in how we approach weather prediction and disaster preparedness, pushing early warning systems towards a new generation. By focusing on the potential impacts rather than just the weather conditions, IBF offers a more comprehensive and actionable framework for mitigating the adverse effects of weather events.

To learn more about extreme heat, check out this Geoversity video on risk perception of extreme heat.