Land Administration Systems

Promoting sustainability with efficient land management

6 min

In another article entititled From Paper to Pixel: The Challenge and Vision of Survey Plan Digitization we gave the background on the vision for transforming land administration records – which historically can exist on everything from cloth to paper to foil – into digital formats. In this article, we describe the solution traditionally used by organizations seeking to digitize old plans. We will then outline a promising new solution.

Many organizations have struggled (or continue to do so) with the above challenge and have sought ways to address it. The classical solution adopted by many is to:

1. Produce high-quality digital scans of the plan,

2. Georeference the obtained image through established procedures - using known ground control points through image processing or GIS software,

3. Apply automated line tracing or manual procedures to digitize (and consequently georeference) the line art in the survey plan,

4. Construct from the acquired linestrings the parcel polygons that are the wanted geospatial features to hold in a geospatial repository and

5. Extract as well the attribute data either through automated procedures (possibly involving OCR or ML techniques) or manual procedures and linking the acquired attribute data to the geospatial data obtained for the survey plan.

Our counterpart GLSC initiated this type of work some time ago, and image scans for almost all survey plans in stock were produced. Steps 2 and 3 above proved to be more difficult to complete and progress has been slow. Furthermore, the resulting data has shown to have rather highly variable quality, providing rather little opportunity for effective quality control.

One specific critique on the classical solution, certainly in the climatic conditions in which our counterpart organization operates, is that the digitization process captures data from documents that have become affected by ageing, wear and tear.

Figure 2 Three survey plans that have become affected by humid conditions over time.

Our first observation in this domain is that diligent surveyor work, of ancient or more recent date alike, produces substantially precise data that the classical solution approach hardly captures, and in a way does not do justice to. This case is illustrated below, in Figure 3. From it, we concluded that one can also reconstruct the geospatial (lot) feature from an exhaustive list of side lengths and bearings by circumnavigation of its boundary from a chosen starting point. This method we call vector chasing.

Figure 3 Left: A plan for a single tract, showing the typical data collected by surveyors as side lengths and bearings, and relative positioning to monuments (constructed or already present) in the terrain. Personal data details intentionally hidden. Right: The “vector chasing” method used in the proposed solution. Observe that typically it finds no closure, meaning that start and end point do not coincide. Their distance is a quality metric.

A second observation is that survey plans that initiate the exploitation of an area typically hold a large number of plots, which by their design are often similarly shaped. This case of “land layout cookie cutting” is illustrated in Figure 4. From this observation, we concluded that in such cases often it is not necessary to capture each lot individually when we provide means to specify the repetitive structure of the plan design.

Figure 4 A survey plan for 44 new lots, indicative of plans showing high lot similarity.

To clarify this case, the solution that we propose allows to build a lot specification that essentially says “construct a grid of 2x2 lot blocks, that hold [6,5] by 2 rectangular lots, with dimensions [150,160] by 134 ft, oriented with 33° 37’ 00’’ as primary orientation, and with 20 by 64 ft interblock spacing.” This is made possible through a user interface panel and will produce the 44 lots shown above, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5 User interface for specification of a grid of 2 by 2 lot blocks, of stated dimensions

We subsequently worked to generalize the capability of these lot specifications, allowing more degrees of freedom, and thus bringing better ability to capture other survey plan designs. This typical research and development work led us to identify the need for

Specification types for

o Singular lot,

o Lot block (multiple lots forming a contiguous area), and

o Lot block grid (an N by M spatial array of mutually separated blocks).

Lot types for

o Rectangular lots (all angles square),

o Quadrilateral lots (four sides, opposite sides parallel, angles non-square), and

o Irregular lots (no restrictions on side number, lengths or angles)

Monument types for

o Erected surveyor poles (existing or created, called “paals” in Guyana in memory of Dutch influences),

o Road (crossing) centres, and

o Other monument types.

Relative positioning mechanisms that mimick surveying field operations, and allow to position correctly lots, blocks and grids relative to each other or to identified monuments.

o Colocation, which indicates that one constituting (lot) vertex coincides with some other vertex in the dataset, and

o Distal snapping, which indicates to position a constituting (lot) vertex at a location some specified distance and direction away from some other vertex in the dataset.

A Lot numbering mechanism that allows to rapidly assign numbers to already created lot sets.

A Lot acreage assignation mechanism that allows to copy in the acreage of one or more lots as specified in the survey plan.

All of these functions have been implemented in a workflow implementation that pairs an underlying spatial database with a QGIS plug-in, which allows a data engineer to digitize an existing survey plan with high (and verifiable) accuracy that is faithful to the inputs that surveyors have provided.

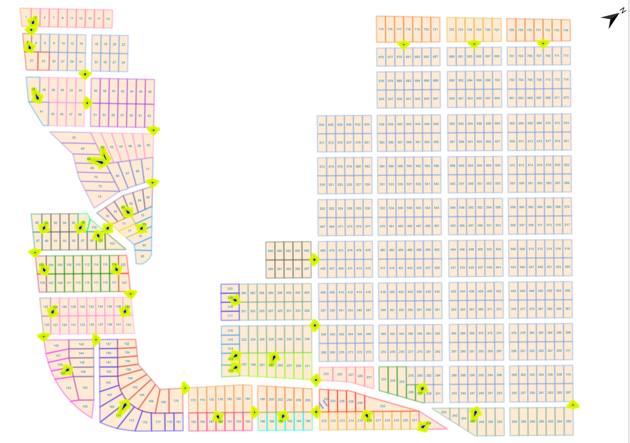

An example is provided below in Figure 6. It shows a completely digitized survey plan with 734 lots, each of which has been given the exact dimensions as provided by surveyor numbers in the original plan, and with interblock spacing dimensions also as stated. The relative positioning steps that were taken show up as yellow-blue (snapping) arrows between pairs of lots.

This survey plan required 51 specifications of lots or lot groups, and (thus) 50 specifications of relative positioning. It took approximately six hours to construct, and this compares fairly well with digitizing effort using the classical approach. Obviously, plans with just one or two lots require really little time to construct: a single lot plan probably will take just in the order of a minute.

Figure 6 Survey plan designed for over 700 residential lots in 1969, some 25 km south of Georgetown, Guyana

The proposed approach is currently being tested in practice, with the digitization of hundreds of plans. We study carefully how well staff can work with the method. While it’s designed to work with a single set of units (one spatial reference system, one unit of length, one way to express bearings), such choices have not been constants over 150+ years of surveying work, and we should allow for different choices made in other eras. We also want to continue work on survey plans that present partial lot circumnavigation and try bring in further data sources to complete lot boundaries.

Finally, our work continues on how to combine multiple surveys that have over time taken place in the same area. Newer surveys may have expanded the lot area as neighbours, they may also have been resurveys that supersede older plans, or they have been executed for lot subdivision work, leading to re-established monuments and measurements. We may be reporting on this in due time.